I must admit that I did not grow up thinking I would be the Chief DEI Officer of L’Oréal North America and influence the global CEO’s vision for inclusion as a member of their DEI Advisory Boards. I’m pretty sure the job didn’t exist as such, but I did know there were people who advocated and supported others and I was surrounded by some of them as members of my family.

I did grow up as a Christian Baptist who believed that “all things happen for a reason” to fulfill the master plan designed for my life. My four siblings and I were raised primarily by our mother. My father was involved in our lives, but she was the force behind all things Angela Guy, for sure.

We lived in New Kensington, PA, a small, rural town about 20 miles north of Pittsburgh. Most of the population identified as white with less than 10% identifying as a person of color. At the age of 3, my family moved into a newly built, low income, affordable housing project a few miles on the outskirts of that town, where the community was more multicultural, and multi-generational. Many of the men were veterans of WWII and worked in the local steel mill like my father. Some men had recently returned from Vietnam and visibly experienced PTSD.

My mother was a caregiver and spent most of her career as a nurse’s aide at the local hospital. A strong work ethic, respect for others, and the importance of family were instilled in us at a young age. While there were only three black-identifying children in my classes from first to sixth grade, I have very fond memories of my childhood. Kids of all ages played together outside; adults sat on their porches at night; neighbors watched out for each other, and our family was filled with love.

I was active in our local church choir and served as an usher. In high school I was a member of the Administrative Club, Afro Club, and Co-captain of the varsity cheerleading squad. I was relatively shy but was always inspired to do what made me happy. I felt a real sense of belonging at that time. Years later, while flipping through my high school yearbook, I noticed comments from some of my white-identifying schoolmates who referred to me as, “a really cool girl who happened to be Black.” Another referred to me as “a real chocolate mess.”

I was always very much aware of my Blackness and immensely proud of it. I had certainly been called the N-word; had people comment about the texture of my hair and the complexion of my skin. I had a teacher tell my class that Black women were at the lowest rung of the societal ladder, and I was reprimanded for debating the point. That said, to be reminded of my Blackness as a condition of my coolness or to have the beauty of my skin tone be jokingly referred to a candy, and in writing, was a permanent reminder of how people might attempt to cover their true perceptions of a person, until they no longer can.

When I was looking at colleges, I met with my guidance counselor to discuss my interest in studying psychology. He was quick to share that he did not ever see me being a psychologist and instead suggested I do something with my hands, like work in the local steel mill. I was highly offended and thought how I could ever do a job that depended on me using my hands to survive. I experienced essential tremors — involuntary movements that are quite visible in one’s hands — most of my life. I went home and told my mother, and she told me something that my siblings and I have lived by as a family mantra: “Never let anyone steal your joy.”

I went to Penn State, main campus, where the population was less than 1% or 2% Black. I majored in psychology and became Recording Secretary and then President of the Delta Sigma Sorority, Inc. Chapter. I also worked part-time at the local steel mill over two summers to raise money for my college education. There were few women who worked in the mill at that time and the conditions were not designed for women, in general. I was, however, exposed to unions and how they advocate for the benefits and well-being of their members. I was also quite clear that I would not have enjoyed that work as a lifelong ambition.

With an interest in industrial psychology, I was curious about the factors that influence productivity. I believed that if you had a deeper understanding of what people needed and the commitment to change policies and practices, you could influence better results, especially if you recognize that needs could vary based upon individuals’ differences and environmental factors.

My very first job relocated me to Youngstown, OH as an Operations Assistant Manager Trainee at a deep discount store called Hill’s Department Store. Youngstown was a bit more metropolitan and diverse than New Kensington at that time. I worked there for a year before I became the Assistant Store Manager at another store location in rural, Tipton, PA. There, I was fully responsible for the operational efficiency of the store from the front door to the back door including supply chain, accounts payable, store maintenance, hiring, training, and developing employees, and overall customer service. It was another very blue-collar community, and I was the only person of color, and woman on the management team.

I spent three years in Retail Store Operations until I received a phone call from Levi Strauss and Company about a career in Retail Sales with their Accessories Division. Initially, I was not interested; however, persistence from them, coaching from my sister who was (and continues to be) the best salesperson I have ever known, and good negotiations from me, resulted in me taking the role as a Sales Trainee in Sterling Heights, Michigan where I relocated and worked under an account executive for a year. I was then assigned to the territory of Nebraska and Iowa and relocated to Omaha. After about a year and a half (and next to no social life), I was recognized as the very first woman to hit every quota and was named Salesperson of the Year. Shortly after, I was relocated back to Michigan.

Designer jeans were entering the market at that time, and Levi’s felt the competitive pressure. They decided to consolidate the Accessories Division into the various jean divisions and I, the Salesperson of the Year, was reduced out of the workforce.

I struggled to understand if I was displaced because of my identity, and when asked why me?, I was told it was a matter of seniority. The barrier at that point was first in, first out. That was my second revelation about someone trying to limit my ability (steal my joy), but it opened the door to incredible opportunities with Johnson & Johnson.

I started working for the J&J Consumer Division as a Sales Representative in Michigan at the Personal Products Company, representing Feminine Hygiene Brands (Stayfree, Carefree, o.b. Tampons, etc.). Surprisingly, there were few women representatives, and most of the buyers were men. I successfully used my in-depth knowledge as the target consumer of the products to drive results early in my role. It also made me question why more buyers for these categories were not women.

Over the course of 19 years, I relocated nine times across North America and worked in various sales positions of increasing responsibility and success. I transferred to their Sales & Logistics Division and led cross functional teams that supported most of the major retailers. I was ambitious and competitive and had a fervent desire to become a vice president. I took an international assignment to fulfill that desire and become the VP of Sales for J&J Canada. In so doing, I gained responsibility for the sales growth and led the sales team across Canada, who represented all the Consumer Product brands across Feminine Care, Wound Care, Oral Care, Baby Care, and Skin Care like Neutrogena, Aveeno, Clean & Clear, and RoC, along with Dermatological Brands like Retin-A and Renova. This broad portfolio of products and the growth of skin care brands is what heightened my exposure to beauty and the lead competitor in the category, L’Oréal.

I recognized how the retail stores in Canada had much more open and accessible beauty merchandising than the U.S. While I was once again the only leader of color on the management team, I was also one of a very few in a leadership position in the market. Retailers were receptive, engaging, and welcomed my perspective on how to grow their business. Most people who are underrepresented know the experience of walking into a store or business, and have the personnel look at you, or question your purpose or abilities. I do not recall having that experience while working from Quebec to Vancouver. The sales office was located just outside of Toronto, and I knew no one outside of work, socially. I met someone at an event one night who introduced me to a local church and the church members became my network of friends, all from various Caribbean islands, who remain some of my closest friends to date.

While the business was growing, I was away from the U.S. for five years. September 11 had occurred, and it was increasingly difficult for my family and U.S.-based friends to cross the border without being regularly stopped and car searched.

In my heart, I was ready to come back to the U.S. Quite unexpectedly, I received a phone call about my interest in returning to the U.S., to work for L’Oréal. I paused because I honestly did not see myself fully represented in the known L’Oréal brands and I was tired of being the only one. My doubts shifted when they told me the role was to lead the sales function for the recently acquired and newly created SoftSheen-Carson business, the newly established number one brand which focused primarily on consumers of African descent. The President was a Black-identifying, African American female; the General Manager was European-Greek. I was replacing the head of sales who was a Black-identifying male who would stay to effectively on-board me to the business. It was my first opportunity to work for a company marketing products for people who looked like me. I enthusiastically said yes (with a bit of negotiation) when the offer came through.

Working for a brand where over 90% of the highly committed workforce looked like me was an unbelievable opportunity. I had spent decades of my life being the only one in the room, and when I first walked into that building on the south side of Chicago, there was a full wall mural of Laila Ali, who was a brand ambassador for the Optimum Care Brand. There was a hair salon on the ground level operated by artists who specialized in textured hair. The cafeteria served hot grits and homemade biscuits every morning. L’Oréal also operated the only National Ethnic Hair and Skin institute that comprised of some of the most diverse and highly skilled chemists, researchers, and dermatologists, all located in downtown Chicago.

I was not an expert in textured hair or deeply melanated skin, but I was welcomed and mentored by the diversity of beauty industry leaders of the major Black-owned brands, multi-cultural distributors, suppliers, and retailers.

Over the course of seven years on the SoftSheen-Carson business, I was promoted to SVP of Sales, then SVP General Manager. We had moved the brand from Chicago to New York to reside at the L’Oreal USA home office which allowed me to personally gain a deeper understanding of L’Oréal’s overall portfolio of brands and culture. I felt an incredible acceptance and sense of belonging working on this brand. It was never planned, but truly an experience of a lifetime that taught me so much about running a P&L, the importance of connecting companies to community; intentionally listening and giving employees a voice that might not have been heard; equity and inequities in the way companies and brands operated and is still one of the best jobs I ever had.

Simultaneous to my onboarding, the acquisition of SoftSheen-Carson facilitated L’Oréal’s jump into DEI. Jean Paul Agon, who was CEO for L’Oréal USA before he became global CEO and Chairman, and Ed Bullock, who was a Human Resource Director, discussed the importance of understanding the need to authentically support the Black community as the key consumer of the SoftSheen-Carson portfolio of brands. It was through Ed’s vision and Jean Paul’s leadership that the DEI Strategy began. When Jean Paul became Global Chairman, he rolled out DEI globally, as it is today.

After seven years on SoftSheen-Carson, Frédéric Rozé, who was CEO of L’Oréal North America at the time, asked what I thought about leading the DEI Strategy, as Ed was preparing for retirement. I was reluctant because I did not think the company was very inclusive across the brands and I did not think DEI should be an HR function. DEI needed to be about the total business, and I reminded him that I was a business leader, not an HR professional. He respectfully agreed and declared that was the reason he wanted me in the role. He saw DEI as a business imperative and recognized the opportunities to broaden its reach within and across the company portfolio of brands, while advancing our engagement externally. So, I took the job focused on the U.S. at the time.

When Jean Paul Agon was Global CEO, he started talking about the importance of having gender equity at every level and equal pay for equal work across the corporation. It was important for us as the leading beauty company whose primary consumer identified as female, to be authentic in our support, development, and advancement of women. He, in partnership with the Head of HR, Jean Claude LeGrand, broadened that reach to include Disability, LGBTQIA+, Social, Economic Multicultural, Origins, Generations, and Military status differences.

At L’Oréal, we measure what we treasure. As a business leader now responsible for DEI, there was a need to broaden our metrics beyond employee representation within teams and suppliers to all dimensions that employees were willing to voluntarily disclose and benchmark our representation to the marketplace. We began participating in external surveys to understand how we faired against our competition and the marketplace. For the past eight years, L’Oréal has partnered with EDGE Strategy across its biggest markets, to conduct a global benchmark on the equity of its policies and practices related to gender and the additional diverse dimensions that were being tracked. This level of commitment is consistent with L’Oréal’s ambition to create beauty that moves the world. Consistently challenging the company’s ability to see, support, connect, and build a sense of pride for its employees and consumers is what inspires the inner beauty that moves us all.

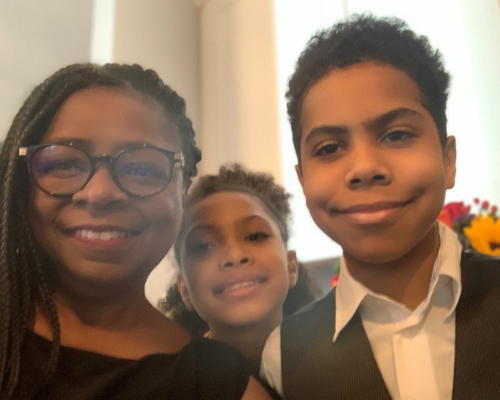

Over the last 12 years that I have spent leading the expanded DEI Strategy and supporting the Global DEI work, I was promoted to Chief DEI Officer, North America to include Canada. The DEI Department in the U.S. grew in people, resources, and funding, and so did my family! In the last 10 years, I became a parent to my 5 year old son and 4 year old daughter, now 15 and 14-years-old respectively, and have learned to appreciate what they have been able to teach me as a working parent, the influence of social media, the importance of flexible work, and ensuring I am contributing to a sustainable world where my children, nieces, and nephews can thrive.

Following my retirement, I was invited to continue my influence as a member of the L’Oréal Corporate DEI Advisory Board, Co-Chaired by Global CEO, Nicolas Hieronimus, and the L’Oréal North America DEI Advisory Board, co-Chaired by David Greenberg, CEO L’Oréal North America. I never imagined how my desire to understand and influence productivity in workplaces would send me through a career journey rich in experiences that validate the importance of inclusion and how understanding the diversity of people, places, and things can influence their productivity. There was a reason I experienced all that I did, and it is increasingly clear to me that part of the master plan for my life’s purpose was to do this work and I am honored to have done so.

Angela Guy is CEW’s 2024 Catalyst for Change Award Honoree. Celebrate her and this year’s Achiever Award Honorees on April 25 in Manhattan.